It’s not worthy of panic yet, but it’s time to think about the AI war that is about to disrupt society.

In the last few months, the capabilities of large language models, such as ChatGPT, have advanced far faster than even the most exuberant predictions. The capabilities of the best commercial models this month may be freely available on everyone’s laptops next month. We need to think about what that means.

This essay describes why apparent “reasoning” in large language models emerges as a byproduct of modeling language structures, and how hackers will use reasoning machines.

Large language models are accidental reasoning engines

Large language models are trained on freely accessible text on the internet — ebooks, Wikipedia, forums, and websites. During training, the algorithms look for patterns in the language to form statistical models of how language is structured. They never copy literal text; they only gather statistics about how words, sentences, phrases, and paragraphs are assembled and structured.1

Yet the trained models often appear to understand our prompts, can analyze a subject, and produce responses that seem to be the result of a reasoning process. Even a few experts in the field have questioned whether the algorithms are partially conscious or sentient.

The problem in questioning their sentience is that nobody understands what consciousness or sentience is. Each of us has inner, subjective feelings, and our own consciousness is intuitively obvious. But what is it? It’s one of a few questions for which science hasn’t the faintest hint of a clue. There are models of how human consciousness works, and tests exist that try to detect it, but those do not help us understand the substance of consciousness any more than the equations of fluid dynamics help us understand what air or water is made of.

We do, however, understand how computers work. We invented them.

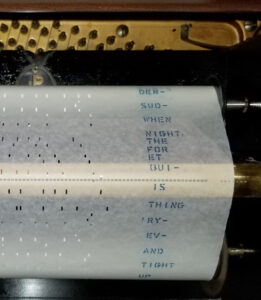

Imagine a player piano that makes piano music without human intervention by reading the holes in a roll of paper. The roll of paper is analogous to a computer program and the piano is like a processor executing the instructions. The piano never invents flourishes that are not encoded in its paper roll. The piano is neither happy playing ragtime nor wistful playing the blues. Likewise, there is no evidence that a computer processor has any inner experiences when executing its instructions.

Let’s not ask about consciousness or sentience in language models, because embedded in the question is the false assumption that we know what all those words mean. Instead, let’s ask how it is that large language models can appear to solve problems through reasoning without appealing to anthropomorphic assumptions.

The short answer is that large language models can exhibit reasoning as an accidental byproduct of arranging words2 into language structures that it learned from examining text on the internet.

For example, we humans often say things such as “If you come over, I’ll make dinner.” Or “When that new phone model is released, I’ll be first in line to buy it.” The internet has gazillions of examples of such phrases with this structure:

- if/when {condition} {consequent}

This is the structure of a logical conditional statement. It’s a fragment of logic that can be combined with other fragments of logic to form a chain of reasoning. A large language model encounters this pattern so many times during training that it learns to recognize and generalize the pattern.

And that example only scratches the surface. Language models learn larger structures that form hierarchies of structures. They learn structures that we intuitively recognize and patterns that we humans cannot name. All of their training gets distilled into a collection of statistical rules.

When you give a prompt to a large language model, it compares how each word in the prompt, taken in context, matches its statistical tables. New words are calculated and arranged in language structures that it discovered in its training. Because it’s hard for our human brains to comprehend the extensive underlying statistics, it appears to us as though the machine “understands” the prompt.

In formulating responses based on language structures, it accidentally creates sentences that are logical statements in chains of reasoning. It’s not reasoning in the way that humans reason. It’s not intentional. It’s as if the algorithm employed reasoning. The net result is the same.

Because the large language models have no subject understanding, the logical statements they produce will have correct linguistic and lexical structure but will not necessarily contain correct logical conclusions. This is a transient limitation. As language models are better trained, their internal statistical models will improve and their pseudo-reasoning will more often encapsulate valid conclusions.

Here are the relevant points so far:

- Large language models compute words and structures that are likely to follow the prompt by applying language structure and statistical likelihoods, not from any understanding of the subject matter.3

- Their responses necessarily and accidentally contain chains of reasoning because the structure of reasoning is intrinsically embedded in the structure of language.

Computers amplify human endeavors

So far, computers have been used to amplify human productivity. Computers can’t aspire to their own goals, but they help humans reach theirs.

Not long ago, if you wanted to give a copy of a book to someone, you had to hire a scribe to make a copy, and a month later, you would have one copy of the book to give away. With computer technology, you can post a link on a website and every person on the planet can have their own copy. It has always been the human spirit that creates an idea, while technology amplifies its production and deployment.

But now, computers can be engaged to amplify reasoning, not just production. And that’s a game-changer.

The history of hacking

For all of human history, when one person has a secret, another person wants to steal it.

In neolithic times, you could hide your secret under a rock, but someone else could find it. Four thousand years ago, the pin tumbler lock was invented in Mesopotamia, and lock picking became a thing. A few hundred years later, secrets were written on clay tablets using substitution ciphers. Code-breaking became a thing. Today we have password managers, VPNs, two-factor authentication, authenticator apps, and iris scanners.

The most skilled hackers today use their human reasoning skills to think of unique ways to entice an employee or contractor to click on a malicious link or make a phone call or reveal a password.

That kind of targeted social engineering requires that the hacker collect personal information about key people, then construct some ruse to fool the victim into participating. After the hacker gets access to a victim’s computer, the hacker uses human reasoning skills to investigate how the hacked computer is networked and to search for vulnerabilities in the protections that are in place.

Less skilled hackers use automated scripts to crawl the internet looking for the equivalent of unlocked doors. If an unlocked door is found, the hacker can install other scripts that search for known vulnerabilities in the victim’s computer. Such scripts are typically simple and dumb.

In the new world, a single hacker of any skill level will be able to set an army of language models working out customized strategies for obtaining personal information from potential victims, construct custom email messages, text messages, fake social media activity, and fake websites with fake login screens. With AI, a single hacker can construct and deploy custom scripts that probe the insides of victims’ computers looking for vulnerabilities with human-level reasoning. At scale.

The arms race

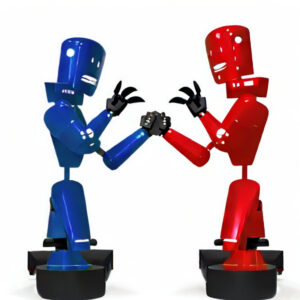

We are at a turning point where bad actors have access to a tool that amplifies not just the production and deployment of their creative effort, but amplifies their reasoning powers.

As hackers learn to use these tools, we can expect an unprecedented increase in hacking successes and a commensurate increase in defensive measures, powered by the AI-assisted amplification of reasoning.

Computer security used to be a matter of individual discipline and vigilance. In the new order, the real battle will rage in the background, AI against AI.

Legislation is futile

There is public demand for AI to be regulated and restrained. But no matter how much we regulate the good actors, nothing will prevent bad actors from obtaining and running large language models.

We’ll survive

It will be disruptive as each side ratchets up their game. But disruption is not extinction. There is no reason to think that AI will take over the world, because AI has no conscious stake in the battle.

It will be the same old battle of good people vs bad actors, with advanced weapons that we do not yet know how to wield.

It’s going to be a wild ride.

Notes

- That does not imply that the models are incapable of plagiarism. They can accidentally reproduce a sequence of words that somebody else has written because there are only a finite number of ways to assemble a stream of relevant words. But even accidental apparent plagiarism can lead to legal troubles. Just ask Led Zeppelin about Stairway to Heaven.

- “Words” is used here for convenience. The models work with units of text called “tokens.” Some are words and others are sequences of characters that form parts of words.

- We’re talking about the language model per se. Providers may enclose their models in layers of pre- and post filters to detect abuse or to handle certain classes of prompts in a subject-specific way.

Leave a Reply